Breaking The Norm

Isadora Neves Marques on Becoming Male in the Middle Ages

After an impressive European festival run, Isadora Neves Marques’ newest short celebrates its North-American premiere at the New York Film Festival this week. In an interview with Līga Pozarska, she talks about (in)fertility, couple dynamics and gender roles.

Asked about his feelings on carrying an ovary implant in his body, the cis male protagonist in Becoming Male in the Middle Ages takes a brief moment and replies: “It’s abstract. It’s an organ. I don’t think much about it.” When discussing this scene with writer-director Isadora Neves Marques, I wondered whether Vicente is devoid of any emotional attachment, pondering the portrayal of pregnancy and the notion of parenthood. “It simply turned out like that in the writing process,” the filmmaker said. “Vicente is lovely but also very absent-minded. He sees the implant as an organ because he does not fully realise the implications of this experiment. He’s just focused on the end goal. He wants to feel motherhood.” Mirene, Vicente’s friend, then asks what’s next: waiting.

Vicente and Carl, Mirene and André, are two couples simultaneously trying to have a biological child in Neves Marques’ award-winning film. Marques remains faithful to their previously explored interests, interweaving environmental issues, technology, and gender expectations in a dense fabula. Their 2019 film The Bite dealt with genetically engineered mosquitoes and a polyamorous relationship. Its predecessor, Exterminator Seed, revolved around an oil spill contaminating the Brazilian coast.

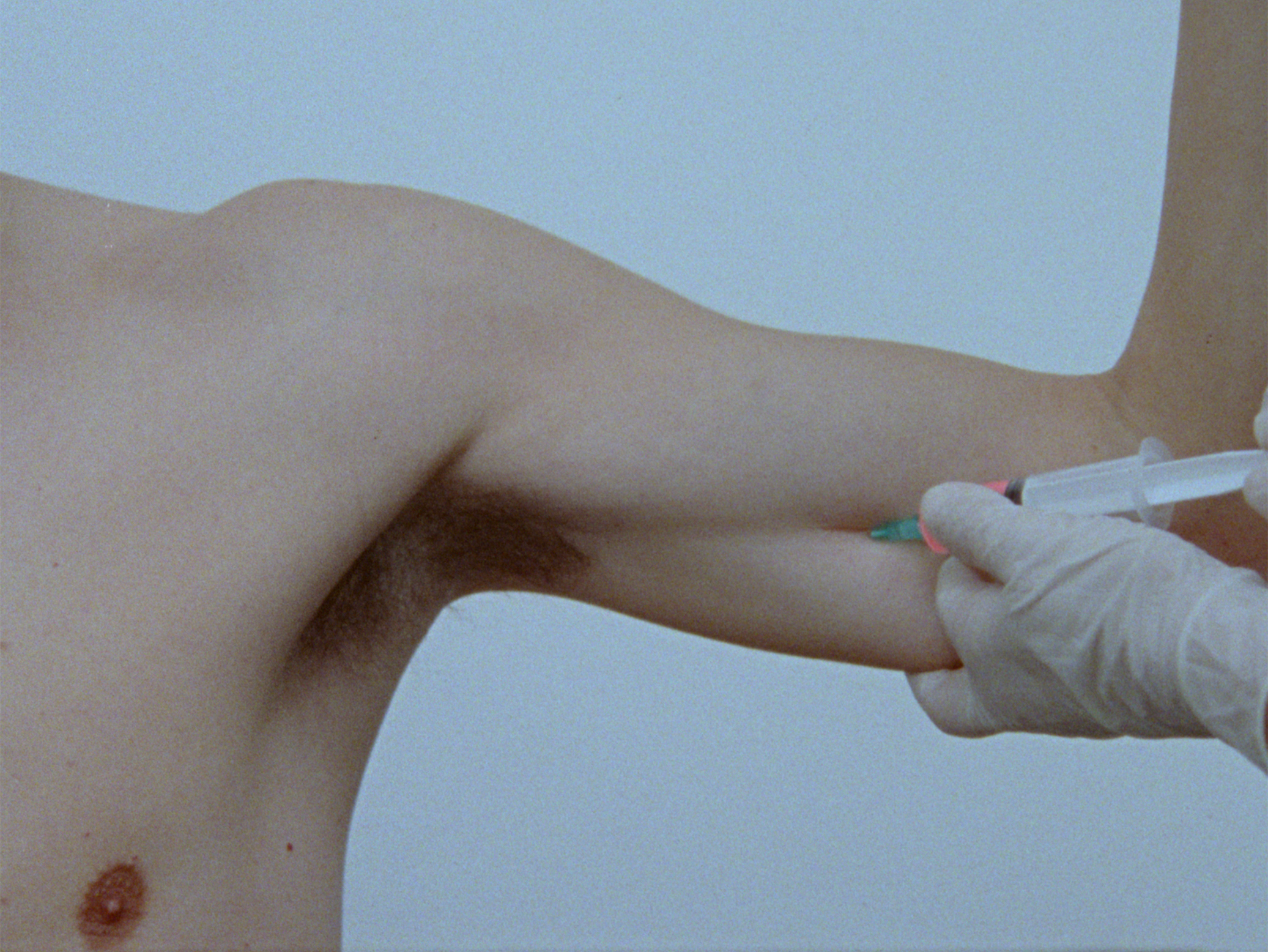

“I was asking myself why the ovary doesn’t go into a cis male’s body. Does the body accept the organ or not? That was the starting point for this film,” elaborates Neves Marques, who was inspired by people in their circle of friends either undergoing IVF or considering having a child after a long time of not wanting one. Given this semi-biographical aspect, it made sense for the filmmaker to star as Vicente. “Not part of the plan initially, but I simply couldn’t find that actor for the role.”

Differing Sensibilities

The story of both couples’ struggles develops from Mirene’s perspective. “I wanted a female voice to channel the story in the middle of all these men,” says Neves Marques, adding that Isabel Costa, who portrays Mirene, is blessed with a tender but firm voice, perfect for a narrator. Mirene’s character is strong-willed, straightforward, and opinionated, “but not always right.”

At the film’s core, doing the emotional labor for Vicente, Mirene primarily processes all that is happening within this group of friends. “She disagrees with a lot of stuff.” At one point, she hints that her gay friends are “privileged” and “self-obsessed”. Unwillingly, while being supportive, a sense of unfairness sneaks into their conversations. Vicente won’t even have to endure morning sickness, and Mirene feels robbed of the same reproductive luck. “She’s confronted, questioning herself: Why do I feel this injustice when I never even wanted a baby to begin with?” says Neves Marques. Her voice-over reveals that André wanted one, so she reconsidered after entering her thirties. Re-examining one’s standings on family comes with an extra burden once crossing a certain age threshold, the sound of the biological clock relentlessly ticking in the background. “This confrontation between desire and age is a complicated reality, especially for women. It becomes a pressing issue.”

Becoming Male in the Middle Ages (Isadora Neves Marques, 2022)

While a burning concern for many, it’s a matter of life and death for some. Becoming Male in the Middle Ages is a ruthlessly paradoxical film where possibilities and impossibilities coexist: modern medicine that attempts to trick genetics and biology (hence lab-grown meat and male pregnancy) still falls short when confronted with infertility and cancer. After extensive research on ovarian transplant procedures, Neves Marques realised that they are mainly performed on women battling cancer. Once done with chemo and having successfully killed the cancer cells, ovaries are often reimplanted. “It’s a tragic but beautiful image—life and death in the same sentence. You’re talking about an organ that provides life while facing potential death. It’s very violent.”

Contrary to Mirene, Vincente and Carl don’t delve into the moral and philosophical aspects of this life-death confrontation and refer to their donor(s) in an unattached, even conceptual manner, using words that are nothing but a strain of anatomical terms — “ovary”, “belly”, “surrogate”, and “implant”. “There is that feeling that for the gay couple, the female body is ignorant,” says Neves Marques. “However, it’s not a judgment on an individual’s sensitivity or lack of it. It is simply an indication of the emotional distance each couple and each person is allowing themselves to feel.”

Deceiving Masculinity

Vicente’s body cannot carry the ovary implant, whereas André cannot impregnate his partner due to low sperm motility caused by increased exposure to environmental pollution. In the stereotypical sense of this term, Vicente and André are both emasculated. “Though some of these aspects happened unintentionally during the writing process, the film does make strong points about the crisis (and toxicness) of masculinity,” further elaborates the filmmaker.

In public discourse and popular culture, male infertility is a subject that largely remains in the shadows. “The common expectation is that when problems with insemination occur, it’s the woman’s fault. In reality, there are more cases of male infertility, so I wanted to play with this prejudice and juggle the expectations around reproduction and health.” Consequently, the failure of having a baby hits differently for Vicente as he had invested both body and heart in providing the host body for the implant. “There is something feminine about him and his desires. But why? Why is it feminine? Just because he wants to have a baby?”

Becoming Male in the Middle Ages (Isadora Neves Marques, 2022)

While Vicente’s case challenges the stagnating conservative views on gender roles, André’s case, as Mirene remarks in the film, is “more political” regarding society’s general views on what constitutes masculinity. Take, for instance, the scene with the dildo, which falls out of the couple’s bed while they are making love. A man’s arm reaches for it and affectionately caresses the pink tool. Does it represent some ideal of masculinity for André? “I’ve heard different interpretations about this scene. It’s also an example of how open the couple’s relationship is. And you don’t even know who’s using the dildo on whom. It can be read both ways, as a phallic symbol or a sign of a very open sexual relationship. I’m happy with both readings. I’m not going to say which one I prefer.”

By diminishing the masculine and feminine constructs, these heroes are liberated from the frames of expected behaviours, thus having the freedom to act on their desires rather than programmed puppets of society.

Intertextual Tides

Becoming Male in the Middle Ages starts in soft summer daylight and resumes in twilight, with wind-breaking ocean waves. After successfully collaborating on The Bite, Isadora Neves Marques again collaborated with director of photography Marta Simões to sync the characters and the city life of Lisbon to nature. “We wanted to film the natural elements— the clouds, the park, the trees—more than the city itself. Marta is very sensitive to 16mm film, and we dialogue very well; we both like to aim for a warm and soft image. When the story seemed too classical and the structure too simple, Simões gave me the confidence to stick to my initial vision.”

“That’s very mildly funny,” replies the filmmaker when we discuss the full moon scene, in which André points out that the moon’s position might not be the best period for impregnation. Despite all the medical and logical solutions they seek, two rational people put their faith in something ephemeral. However, Neves Marques’ intention to include the lunar phase’s remark was also pragmatic, connecting their heroes to nature’s cyclicality and observing how they relate to them.

“So why this title?” I ask. “Did you borrow some elements or ideas from the 1997 academic publication by Cohen and Wheeler?” Marques replies: “The book is about medieval queerness. It’s an interesting read, and I was very taken by the title; it felt so beautiful and out of context.” Allegorically, the title reflects on transition, which is entering one’s thirties or forties. One could argue that it’s not technically mid-life, but it certainly feels like a mid-point. In addition, it is a hopeful metaphor. “The Renaissance followed the Middle Ages; that’s also happening in the film. A scientific promise of a different world, different future where the [social] station is no longer attached to gender.”

It’s not the sole moment in the film when books reveal a larger truth about the people who are seen reading them. Mirene is holding Woman on the Edge of Time, a feminist classic written by Marge Piercy, where the author describes a hell of a journey the protagonist Connie goes through in 1970s New York, also envisioning a future where babies are born out of tubes and where there is no place for inequality and discrimination based on gender or race.

Becoming Male in the Middle Ages (Isadora Neves Marques, 2022)

“As a science fiction fan, I wanted to have it there. It made sense that Mirene would be reading that. Maybe she is searching for answers in books and fiction.” Meanwhile, André has Tiago Saraiva’s Fascist Pigs: Technoscientific Organisms and the History of Fascism on his table, in which the author investigates how genetic experiments with agricultural plants and breeding of domestic animals were the essence of the fascist regime’s food independence and land acquisition policies.

After careful examination, André, a vegan, ends up eating a politically correct chunk of a non-cow that’s discussed in the film’s opening sequence. “I wanted to give some hints about his personality and his position on animal rights.” Perhaps in reading this book, André was searching for precedents.

Compromising Artificiality

Mentioned twice in the film, the term ‘artificial’ has at least two shades. At the start, André refers to the non-cow piece of meat, while by the end, Carl uses it in the context of Mirene’s decisive suggestion to form a nuclear family of three grownups and a potential baby. Both interpretations are of equal importance. Artificiality is a sign of progress: bioengineering leads to meat without butchering a cow, while male pregnancy allows Vicente to imagine carrying a baby.

Furthermore, friends becoming family reassures that the family institution is flexible. But artificiality also means something is inherently fake. The lab-grown steak makes André sick, and Vicente’s first implant success is short-lived—an ovary needs a womb. Finally, an unusual family suddenly feels like a foreign concept to otherwise progressive people.

Both couples are going through a relationship crisis paired with inner insecurities: apathy, self-doubt, and fatigue. Nevertheless, in each relationship, someone has always compromised on the “baby question”. By the looks of it, Mirene and André are less likely to survive this. However, the writer-director remarks that the relationship dynamic between the heterosexual couple is equal. In contrast, in the homosexual couple, the balance is “much more gendered”, Carl being the dominant one, while Vicente remains soft and feminine.

“Even Carl ends up having to question himself. He’s exhausted, and he’s the one paying for all of it.” He, who had no problems with artificial meat, is not instantly at ease with the proposed family model. The tables have turned. “We can create our own artificiality,” concludes Mirene. Patience has tested both principal couples. Cancer has put a deadline on women of reproductive age. Suddenly, it’s all about waiting or acting immediately.

Nevertheless, this multilayered story asks curious questions about hormonal research, future bodies, and the climate crisis affecting fertility. Neves Marques concludes: “Our bodies, or any organic bodies, are mutants. They can change. They can be transformed.”