Empire of the Sun

Daydreaming So Vividly About Our Spanish Holidays

Shot in vivid 16mm, Barcelona native Christian Avilés turns a piercing gaze on young British holidaymakers, creating a reverie of surreal seduction out of the real-life phenomenon of balconing.

Modernity, we are told, has become disenchanted—a world governed by reason, in Weberian lore. The “great” British colonial anthropologists like E. B. Tylor and James George Frazer proclaimed magic a false science, with animism, in their view, as the most simplistic form of religious life. We, too, often scoff at the anti-scientific endowment of nature with a soul or spirit. But time and time again, the forcible secularisation of our world fails to persist, and spiritualism lives on in unexpected forms.

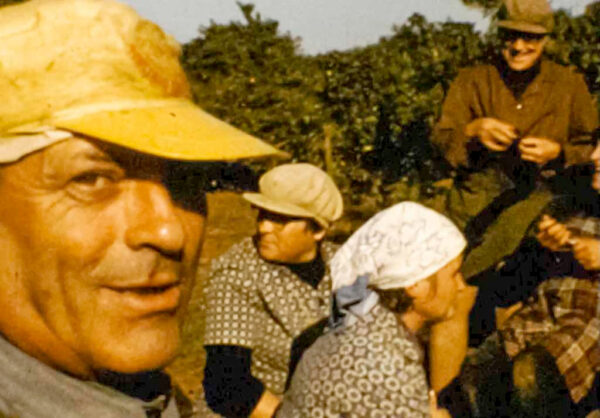

This proposal is taken up by Barcelona native Christian Avilés, who turns a piercing gaze on young British holidaymakers, creating a reverie of surreal seduction out of the real-life phenomenon of balconing—tourists jumping from these eponymous platforms, particularly in Spain’s Balearic Islands. Shot in vivid 16mm, Daydreaming So Vividly About Our Spanish Holidays is Avilés’ first short film, with Mallorca being his fantasy of enchantment and the act of balconing his hierophany (from Greek: hieros, sacred or holy + phainein, to appear or reveal), a manifestation of the sacred in the profane world. David Avecilla’s colouring makes the island setting look like a child’s playset, the palette simultaneously too radiant while maintaining an oneiric veneer, evoking the visual style of Paul Briganti’s short (and eventual feature) Greener Grass from 2015.

Our guide, Sam, starts in his home in oh-most-drab, penumbric Liverpool, the walls the colour of blue-grey sludge, darkness practically closing in on him despite the summer months. An interaction between the teen and his mother at the dinner table is staged performatively, their bodies turned out toward the camera. To cheer up her glum son, his mother offers him an early birthday present: a literal golden ticket for a flight to Mallorca. The envelope reflects a gentle, gleaming ripple of light across his face. As if its caress stirs up the spirit England’s disconsolate climate has pushed into hibernation. As an off-screen narrator, Sam explains how, after a blackout one day, he began to move toward a warm, welcoming patch of swirling light emerging from darkness. But then, just as he was about to reach the light, he says, he “resurrected.”

His voice comes from the void in heavy reverb, mirroring a sort of disembodied God over images of a summer resort. He explains that young Brits come to Mallorca to seek the sun, “everlasting inhaling and exhaling light.” From a canted angle, we see a young woman lying face up on her hotel bed, her full-body scarlet sunburn a red badge of courage. Another sunbathes at the pool, the background melting away until all that remains is a halo around her sleeping head. Avilés is not afraid to play with opacity—to blend and superimpose—to create this unironically half-otherworldly, half-2000s music video effect. The bewitching shine of the sun on the water is layered onto the vibrant neon lights of the night, the natural rays still lingering even through the long evening hours.

Still out of sight, our protagonist evokes the Icarus myth by imagining, in a soporific voiceover, that he is a “creature with white and gold feathered wings” flying too close to the sun. But the inevitable burning of his wings is not born of an act of hubris—instead, it is a final absorption into our stately star, a kind of eschatological glorification. In this sequence, the pattern of the sun on water returns, this time blurry and less distinct, the repeated motif now more of an elicitation of opposing Jungian archetypes: light and dark. The filmmaker, who also composed the music, settles on the trancelike quality of minor thirds played with the timbre of a music box as a soundtrack for the island daydream. The aural-visual combination of music, voiceover, and light arouses a meditative state of surrender.

Soon enough, the warmth calls too strongly through that ubiquitous, swirling patch of light burned into the backs of eyelids. But to reach that gaseous glow, the tourists must move nearer to it. In a medium close-up, a young man basks in the radiance of the sun, the camera’s zoom pressing ever slowly forward as he stands on his hotel balcony four stories up. With the sequence switching between this and the perspective of those on the ground looking up, we hear the tinkle of windchimes. The sun, cast as a sparkling illumination in the hotel pool, draws him to look down at that hypnotic luminescence, calmly climb over the balcony ledge, and jump toward it (“Watch me, I’m going to disappear into the sun”—a tongue-in-cheek reference to Lorde’s “Liability”?). Perhaps the film’s most haunting shot is that of a group of other young Brits, transfixed, silently holding their smartphones up to record the teen’s fall from grace. They have been enchanted by a second object emitting light, that grand handheld oracle we cannot live without.

Later, we learn that six tourists died in the same act. The Mallorcan resort, Hotel Kokoro Park (in Japanese, kokoro refers to a monism of soul, mind, and heart) is the corporeal body upon which these divine stigmata form: la herida luminosa, or “the luminous wound,” as goes the work’s original title. In the film’s short coda, a TV announcer reports that “alcohol and drugs are to blame,” according to the local government. But a Spanish EMT ponders whether this phenomenon is an intergenerational curse cast on the British by subjugated tribal people. The very possibility would make Tylor and Frazer roll over in their graves.

At the airport gate, a pool-weary group of young tourists sings an elegiac choral hymn set to flowing harp, their under-eye sunburns a devout self-flagellation of the flesh worn proudly like Korean skincare masks: “I don’t mind the pain, I still want it all.” They smile knowingly at each other, as if sharing an inside joke—eerily, like pilgrims lamenting their return to the profane world. It seems as though if you jump toward the sun and live to tell the tale, injuries and all, the spirit of enchantment lives within you, forever.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #3—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!