In Cold Blood

Incident

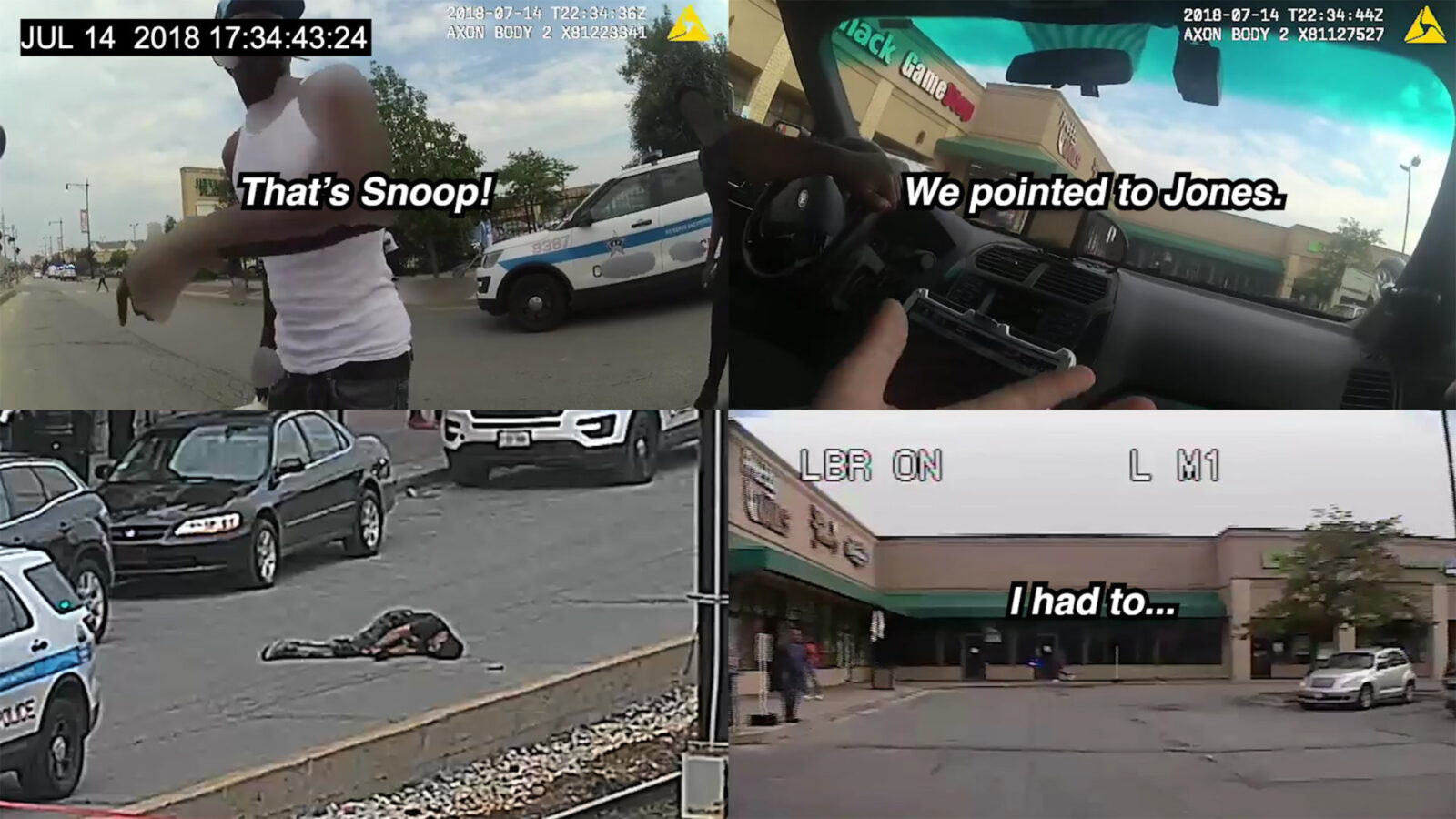

Through a composite montage of images from surveillance footage and body-cams, Bill Morrison delivers a chilling political investigation in search of the truth after a Black man is killed by police on the street.

The day is 14th June of 2018. Pre-Covid, before the George Floyd case crawled its way out of a Minneapolis gutter, but after Donald Trump’s election as the 45th president of the United States. It’s an unbearably warm afternoon in Chicago, Illinois; some may even say it’s too hot. The city is hosting its typical summer happenings. The police patrol one of the streets for criminal activities; civilians mind their business and saunter in different directions; restaurants and shops welcome their first customers—all of this has been recorded by one of the street cameras, and the footage reveals that an unspeakable thing has happened.

Then, thanks to another example of American surveillance, we can spot a Chicago barber, a black man called Harith “Snoop” Augustus, leaving his barbershop to run a few errands. Fifteen minutes later, he is shot by one of the policemen. It’s another day in this urban jungle that will change nothing for the entire US. However, it will change everything for Augustus, his five-year-old daughter, family, friends, colleagues, and neighbours. And, for us, the audience of Bill Morrison’s latest documentary short, Incident, which screened at this year’s Vilnius International Short Film Festival, the event became an unforgettable experience. Not only does it capture what’s clearly an act of police violence, but it also offers an example of how well such footage can be put together into a powerful whole.

For another couple of minutes, Augustus will also lay dying with no one willing to help. Bystanders will then shout at the police to call an ambulance. But no one is going to do anything. Also, thanks to a few swift close-ups, we can spot his last breath. And then, for another twenty minutes of Incident, we will have to watch Augustus’ corpse lying in the middle of the street. Left there, disgraced and exposed to the onlookers’ all-too-obvious gaze.

With this powerful, short introduction, Incident establishes a complex, thirty-minute narrative that needs to be carefully followed by the audience. Just after Augustus’ death, the film slightly backtracks to give the viewer an exhaustive background description of everything that happened. Although one is compelled to read a lot of informative subtitles, having it all laid out like that allows the viewer to learn more about American laws and the way they supplement racist social dynamics.

To make Incident, Morrison purely relies on the video footage he has collected. As we will see, even one of the witnesses is appalled. “[Snoop] was murdered in cold blood,” he cries and inadvertently recalls the title of Truman Capote’s legendary reportage. Morrison’s film implies that manslaughter was committed here. But is that an objective truth? Despite the dry facts, the film’s non-biased form (strictly based on unrelated footage from various sources) does not propose any precocious judgments.

Contrarily, the director weaves a visual and complex experience, where four types of footage (surveillance, police body cams, bypasser’s personal recordings, and car cameras) are displayed simultaneously on split-screen. Such composition allows Morrison to create a compelling image from various perspectives, as every viewpoint sheds different colours of light on the same occurrence. Yes, everything we see coalesces into a logical whole, but it is up to the spectator to come up with their conclusions. Besides, watching Morrison’s collage already suggests a rewatch to cope with the intensity of it all. During the first viewing, it becomes obvious that its multi-faceted structure wouldn’t allow us to spot all the nuances. In this case, it’s not about finding reinterpretations of the recorded incident but comprehending the actual truth about policemen’s actions.

Throughout the years, American history has proven how the bulk of US society, including law enforcement, feels persisting animosity towards people of colour. Nonetheless, the same hostility is still discernible in Incident thanks to one of the policeman’s body cameras. It’s an audacious choice to attach this perspective, as it pictures the reverse of the same coin. We see that instead of peacefully approaching the victim, the police rapidly (and violently) tried to handcuff Augustus. The reason? They spotted a gun hidden in his trousers. He had permission for it, yet no one was eager to listen. The explanation for their behaviour? He was a Black American.

After so many decades, the film indicates that nothing has changed. Yet, this documentary can finally make a difference due to the vital power of the film image, which has never been so tactile. Here, every detail is just another substantial addition; here, every dialogue discreetly outlines the social tensions in US society. In other words, even five years after the eponymous incident happened, we feel like actual participants—like we just experienced the shooting, and now we are trying to untangle the intricate layers covering it.

With all of this in mind, it’s simple to pass judgement on the white policeman. But is it purely his fault? It’s a topsy-turvy situation, and Morrison himself is somewhat sceptical about it. Thus, he is diligent enough to deliberately show us a couple of policemen’s POVs. When he introduces us to other heroes of this tragic play, the director underlines that most of the patrolling cops (including the shooter) have had only a year of experience. So, again, is such a person prepared for such radical circumstances?

Clearly, as various recordings prove, the policeman called the shots with aplomb, he poorly interpreted the situation, and he immediately treated Augustus as a potential endangerment only because he was Black. Regardless, we later watch the footage of his bodycam: the stress and regret are also there. He constantly repeats his exaggeration that Augustus was belligerent towards them (as they say, the lie repeated thousands of times becomes a truth). He somehow wants to believe that; he doesn’t want to feel guilty about killing an innocent person (Augustus didn’t even pull his gun out). After all, there is another scene, which, in a reasonably illustrative slow-motion, shows the same policeman confiscating the weapon from the target’s pocket. But, the same question recurs: Is he really the “bad guy”? Focusing on his reactions and instant guilt allows us to assume that there is still a suffering human being behind the bulletproof vest. Nonetheless, Incident does not give us any specific hints or explanations regarding his disturbing behaviour. Ultimately, our reading is determined by our perspectives and the types of emotional empathy we individually possess.

The policeman is responsible, yet he is also a product of Trumpian hate speech, of hundreds of years built on loathing people of colour and stereotyping them, of being raised on the country’s soil, which is sowed with hatred and prejudice. He saw what he was taught to notice: he succeeded in finding a peril in a Black man. Why? The answer is simple: from the millisecond he had caught sight of him, the policeman never treated Augustus as an equal human being. After going through all the footage in Incident, it can be argued that the policeman is a victim of the system as much as Augustus is. No one taught him how to handle such situations, while his primal antipathy towards the man’s skin pigment has only affected his situational awareness. The only difference is that one of them is now dead. In a sense, every person related to this unfortunate event has been an aggrieved party.

Augustus is no longer alive only because the US system does not learn from its endless mistakes. Incident is not about understanding the police’s technical procedures or why the victim believed that he needed a gun to, presumably, protect himself. It aspires to make the audience understand why we can no longer write and talk about Augustus in the present tense. And there is nothing more righteous that the documentary and its filmmakers can do to honour the incident’s participant(s).

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #3—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!