Lies Alive

Stephen Vuillemin on A Kind of Testament

Now nominated for Talking Shorts’ New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025, Stephen Vuillemin talks about his gorgeously animated short film A Kind of Testament.

While many have tried, nobody’s yet untangled the knot that ties together images and truth. Whether it’s the relationship of painting towards landscape or that between photography and its subject, what goes on between representation and the present remains, ultimately, a mystery. This unsolvable riddle certainly inspired French filmmaker Stephen Vuillemin to make his first short film and perhaps even to name it so tellingly.

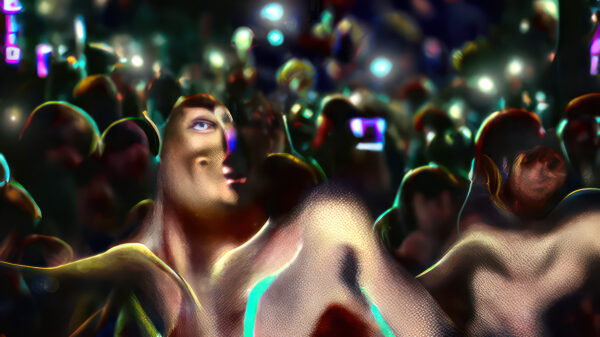

A Kind of Testament opens with an upwards pan on flower blossoms; detailed and rich in colour, these bi-coloured tulips and roses pulsate as living beings. Once in the hands of the film’s protagonist—a young girl with long shiny black hair—they wither and die almost instantly, as a downward pan shows us a pale blob where the vibrant colours used to be, and flies; lots of flies. The treacherous dance between ardent life and banal death is the opening gambit of the gorgeously animated A Kind of Testament and alludes to the double entendre of the image as such: it can be alive, and it can also be a lie.

Before making his first film, Vuillemin had been a comic book author and illustrator, and his 2011 webcomic Lycéennes made him a well-known name. When I asked him about his approach to storytelling as an illustrator and animation director, he explained that A Kind of Testament first came to him in film form, storyless. I admit his response surprised me not only because we associate the medium of film with a narrative journey told through moving pictures but also because the plot of the short is already complex, layered, and meandering.

It begins with a rather peculiar coincidence: the (nameless) brunette protagonist, voiced by Naomi Yang, stumbles across a website domain with her (anonymised) name and a list of cartoon animations replicating none other than her own Facebook photos. No wonder the disturbing nature of her finding sends her down a spiral, researching the animations. How come they even exist without her knowledge? A touch of conspiracy and a glimpse of fate aided a full-blown identity crisis. Yet, the intricacy of the story here is matched only by the animation’s lavish visual style.

“For a while, I had ideas for the form of the film,” Vuillemin explains. He kept notes, but not the kind you would expect. “They were quite abstract,” he adds, listing examples: “opulence, an air of a Renaissance painting, a plethora of objects that evoke richness.” The 16-minute short comprises animations drawn in such affluent detail that invite us to marvel at what we see, even when it’s an image of decay. Vuillemin uses decorative techniques to beautify and expose the film’s main character and her tumultuous psychological journey when she finds out her identity is compromised, if not stolen. Starting from these more intangible references, he suddenly realised what the film would be about. “I had a sort of Eureka! moment,” he says, “when I thought of using voiceover to give the images a fictional context.” Five actors voice the animation in five different roles. While praising their work, Vuillemin also remarks that voice recording has been exciting because it’s “real-time, as opposed to animation, where you spend days animating one second.” Using this tension between the real and the fictional, the animations were built around the voices, which were “the spine of the film in terms of timing.”

The film’s crescendo sees the young protagonist torn between two existential scenarios in a fierce moral battle between youth and old age. This narrative thread came last, as Vuillemin explains, “to bring in the theme of Vanitas that had something to do with my original wish to evoque richness [through images].” Naturally, his way of describing the film’s plot is also ornate, calling it “a sort of a Russian doll, or a tiramisu of fictions.” I cannot help but ask him whether he’s considered A Kind of Testament in relation to deepfakes. To his initial surprise, I explain my thinking that, as such, deepfakes are a violent act of identity transgression, but while there is also a lack of consent in this short, the discovery of animated selfie-replicas feels much less violent. It helps the protagonist venture into this journey (spiral) of self-discovery.

When speaking of the double nature of images, Vuillemin mentions the importance of placing two forms of image-making in parallel—one character takes selfies, and the other draws animations based on them—yet both of them produce images. Even if we consider selfies documentary-adjacent, animation is associated with fiction and imagination. With his shorts, Vuillemin challenges this divide by bringing the tension between those two parts in close proximity. “What seems most real in the film is the voice-over’s words. I tried to make it sound like a documentary, as if it was a real testimony of a character. Still, it turns out it’s completely fictional: her original selfies never existed in the first place. They only exist in their drawn, animated form, which is the one you see when you see the film. So the animation world turns out to be more real than the documentary world.”

A Kind of Testament (Stephen Vuillemin, 2023)

In addition to the existential angst, the pulsating .gifs and tense sequences in Vuillemin’s images make A Kind of Testament flutter with life. He conceived the film’s storyboard as a succession of illustrations rather than as fully-fledged moving image sequences. “I wanted to only draw key moments and the most striking images, and let the voice-over bind them together,” he adds, alluding perhaps to the close-ups of dying flowers mentioned above or the angst-ridden frames where symbols of death (i.e. skeletons) quite literally take over. In addition to more conventional animated sequences, there are some arresting images that exist like .gifs on repeat. When describing aligning those pulsating gif animations with the animated narrative sequences, the director points out how the latter became “an unrivalled tool for building suspense.” The result is a hybrid form, mesmerising as it clutches and releases the character from the grasp of editing.

After watching A Kind of Testament, a viewer will certainly question their own relation to images, conceptually speaking, but it’s curious to find out that Vuillemin himself has an ambiguous relationship to images. “I don’t think they’re trustworthy, but I still find them fascinating, like the song of the sirens!” He admits that the dichotomy between truth and fiction can be both inspiring and frustrating. “In my film, I’ve tried to close the gap with a lie,” he says, meaning the use of voiceover convincing us that all these animations were made by a woman on her deathbed. But they aren’t. They were made by the director and his team over six years: before the Paris-based Remembers Productions came on board, he worked alone, with no deadline, no pressure, and nobody looking. This independence may have cost him years of free time between commissions, but Vuillemin could hold up every detail to his own scrutiny. “If I wasn’t 100% happy with an idea, a shot, an animation, I would redo it,” he says, “which is something impossible to do within the [more commercial] industry.” So even if the film’s narrator turns out to be unreliable, when she calculates and quantifies the labour it must have taken the animator to make those .gifs, she has a point. “That part—the amount of labour—is real; it did take a lot of time to make this film.”

Is there a place for both truth and images in both our world and in A Kind of Testament? “Lately, I’ve been having a hard time with the arrival of AI-generated pictures,” Vuillemin shares, “especially the ones that mimic the so-called cursed pictures (supposed renditions of a real moment in time but lacking all context), in particular the work of Ron Jafman, the AI alias for Jon Rafman.” Reflecting on the growing role of AI-generated images now, the French director admits he finds it rather sad that we can rarely tell the difference today. His fondness of cursed pictures seems related to nostalgia where “such a strange situation did happen somewhere, at some point in time, and it was captured by a camera,” but what echoes in his words is still the never-ending pursuit of wonder, factual, fictional, or animated.

A Kind of Testament was nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025 at Filmfest Dresden by Mac Andre Arboleda, Daria Janke, Claudius Kesseböhmer, Antoni Konieczny, Marcelina Leigh, and Ebba Yttermyr, the participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #4.

The New Critics & New Audiences Award is a project by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END), hosted by Talking Shorts, and funded by the Creative Europe MEDIA Programme. With the support of This Is Short.