Mommie Nearest

Can you hear me?

Different perceptions of technology serve as a starting point for uncovering intergenerational conflicts and long-forgotten family threads in Anastazja Naumenko’s animated desktop documentary.

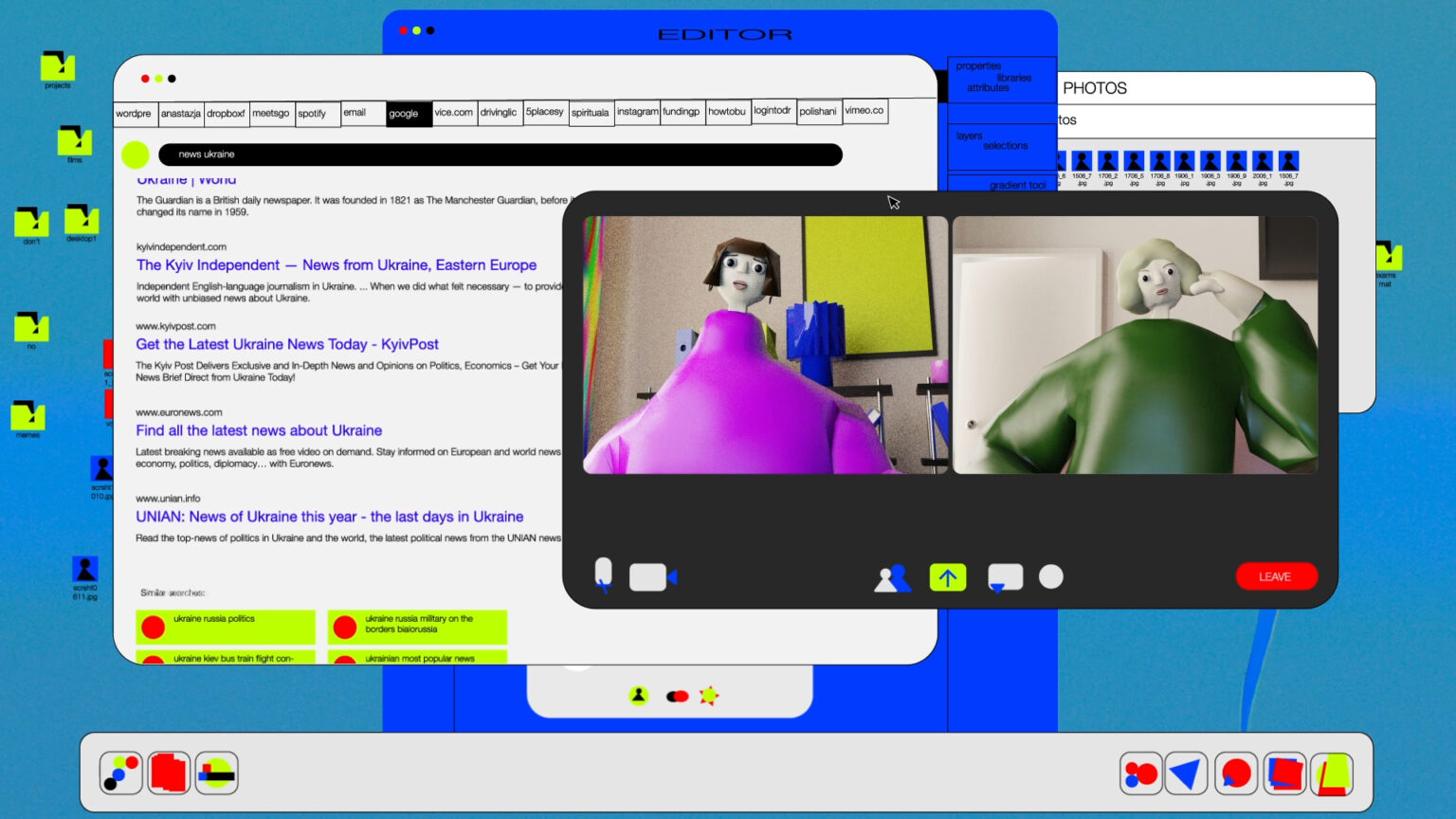

A neon PC desktop filled to the brim with pop-up notifications, instant messaging apps, and browser tabs evocative of the tactile graininess of the internet in the early 2000s. Ambient electronic music plays in the background, as each open window tempts the viewer with the possibility of escaping into a different cyber dimension; guaranteed to keep your mind off the mundanity of holding familial grudges, as emotional nuances keep getting lost in digital translation. Such is the scene set by Polish visual artist and director Anastazja Naumenko’s touching animated short Can you hear me?: a multifaceted digital love letter to all that remains to be said between parent and child, as told through various long-distance video calls between digital nomad Nastia and her well-meaning, albeit scatterbrained Ukrainian mother.

Divided into three chapters—each one named after a different how-to manual on navigating the digital realm—the film follows the tech-savvy Nastia, via a screen recording, as she walks her mother through the basics of using a personal computer, from sharing one’s screen on a video call to copying files from a pendrive. The apparent reversal of the parent-child dynamic implicates the subversion of parental authority, as Nastia takes on the responsibility of holding her mother’s hand in the foreign territory of the internet.

Their scheduled daily video calls are set to the backdrop of the ongoing full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, which Nastia keeps up with via live online reports. The ever-present threat of violence exacerbates the urgency of connection between mother and daughter, who, despite their best efforts, more often than not end up talking past each other. But where Naumenko’s film really shines is in those rare moments of poignant confession, when sincerity seeps through the cracks of the desktop screen, as each woman manages to detach herself from quotidian digressions enough to offer a piece of herself to the other as a token of familial intimacy.

The first of these instances occurs in the opening chapter when Nastia’s mother reveals that her father used to beat her as a child. As she recounts the story of how stealing postcards with a friend earned her a thrashing with the belt, the film recreates her memory on Nastia’s desktop through a series of images, files, and folders. The result paints a profoundly affecting portrait of a grief-stricken daughter trying to make sense of her mother’s latent trauma by following the narrative thread of her pain with her cursor. Lost for words and desperate to fill the crackling silence from the video call, Nastia suggests they move on to the basics of creating an e-mail account.

The film offsets these emotionally harrowing revelations with the all-too-familiar technical lags of a modern Zoom call. Every time an unstable internet connection, glitchy video images, or delayed audio disrupts the conversation on display, the viewer is reminded of the vast physical distance between Nastia and her mother, which is obscured by the immediacy of digital contact. These immaterial constraints notwithstanding, mother and daughter persist in their respective attempts to listen to each other, but the titular question of whether one truly hears the other across digital and emotional fault lines remains open.

The oddball animation style, reminiscent of a digitally polished version of Claymation, aestheticises the generational divide between Nastia’s tech know-how and her mother’s more anachronistic sensibilities by bridging the gap between the virtual and the tangible. Likewise, the simplistic design of the characters—each composed of a comically wide torso, disproportionately small head, and googly eyes—seemingly evokes the elemental nature of the film’s familiar subject matter: familial miscommunication. As over the course of the film mother and daughter become more comfortable divulging individual grievances about their relationship and untold secrets from their shared family history, emotion swells, culminating in a heart-wrenching confession on the former’s part about carrying the heavy burden of motherhood: “I wanted to be a good mother, Nastia,” she admits as the scene cuts to black. “I didn’t even imagine it could be otherwise.”

© Can you hear me? (Anastazja Naumenko, 2025)

The cinematic use of epistolary filmmaking to depict longing for connection in long-distance mother-daughter relationships has its roots in Belgian auteur Chantal Akerman’s autobiographical documentary News from Home (1976), and in British-Palestinian multimedia artist Mona Hatoum’s video piece Measures of Distance (1988). Both films feature voiceovers in which their respective directors read letters written to them by their mothers over a montage, connotative of the emotional gulf between a young woman who has left home to come into her own and the part of herself that she has, however willingly, left behind in the image of her mother. Following in the footsteps of Akerman and Hatoum, Naumenko substitutes written correspondence with recorded face-to-face conversations to make an equally salient observation on the double-edged promise of our fully digitised contemporary world: social media conflates communication with instantaneous connection while also making digital room for unanticipated moments of closeness, like two cursors that come close enough to touch yet remain so far apart.

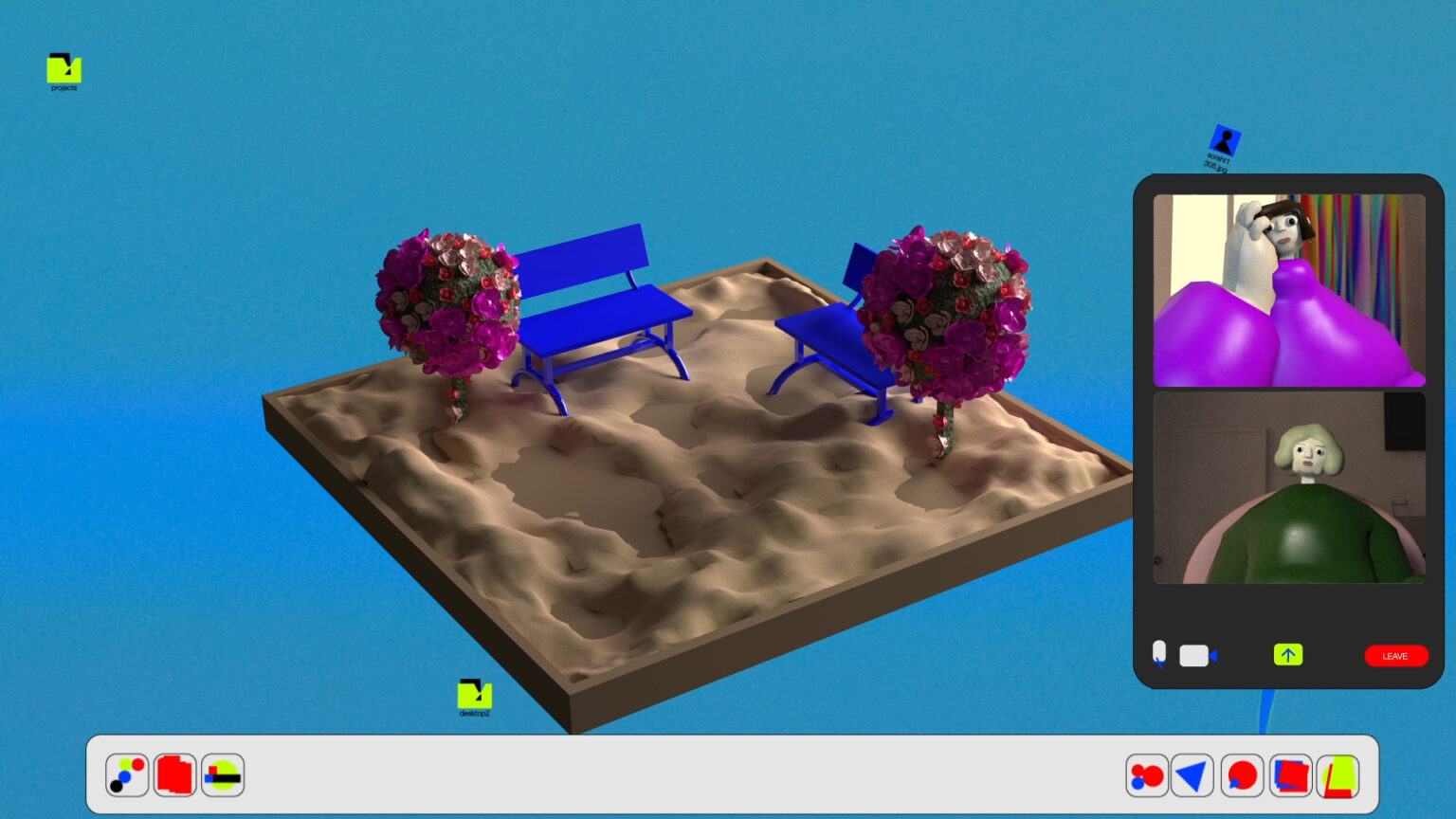

Can you hear me?’s tear-jerker of a final act is a testament to the latter point, in which Nastia’s mother recalls a recent trip to her psychologist’s office, where she was asked to fill an empty sandbox with the various bric-a-brac at hand. Only, she admits, none of the objects fit her liking. In trying to accommodate the peculiarities of her loved ones—from her ex-husband’s unwavering indifference to their children to her mother’s casually cruel lack of regard for her well-being—she realises that her heart has been exhausted of feeling; dented with the weight of other people’s presence, with nothing left to show for itself. On the other side of the screen, a concerned Nastia nods reassuringly, as if finally willing to see her mother’s shortcomings for what they are: not as moral failings on the part of an ill-equipped parental figure who is always obligated to know better but as ripple effects of a life spent submitting to the whims of others at her own expense.

Following this penultimate heart-to-heart, we get a final glimpse of the mother and daughter in the post-credits coda, where Nastia smiles fondly at her mother’s muted ramblings, presumably in acknowledgement of all the words that have fallen—and will presumably continue to fall—on deaf ears between them. “I’ve missed you,” she tells her in earnest. Reaching out across the digital ether once again, willing to risk being misunderstood for the slim chance of being heard but for a moment.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #8—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Michaël Van Remoortere.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!