Not So Gentle Giants

Alessandro Novelli on De Imperio

For all its doom and gloom, Alessandro Novelli’s work is marked by a stark beauty. In De Imperio, we enter a world of empire and control.

Alessandro Novelli cares about power, and he’s asking if I’m aware of mine. “At a certain point, it’s the critic who ‘makes’ the work of art, not the artist,” he cautions me. It’s a more foreboding start to my first-ever interview than I had imagined, but given Novelli’s small yet impressive body of work, it shouldn’t come as a surprise. Across a series of animated shorts, the Italian writer-director-animator has shone his particular light on themes of control and agency, and now he’s directing it at me.

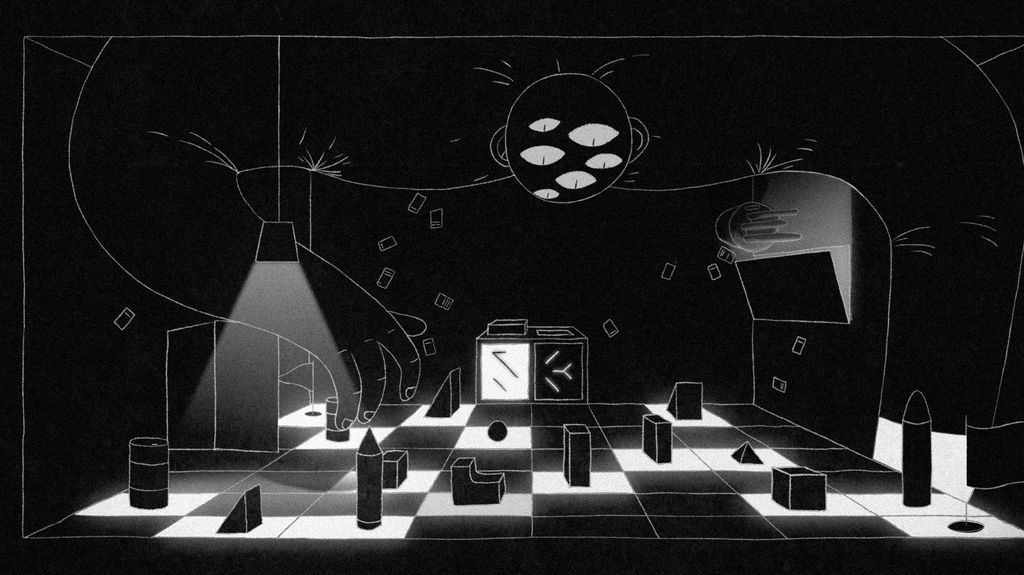

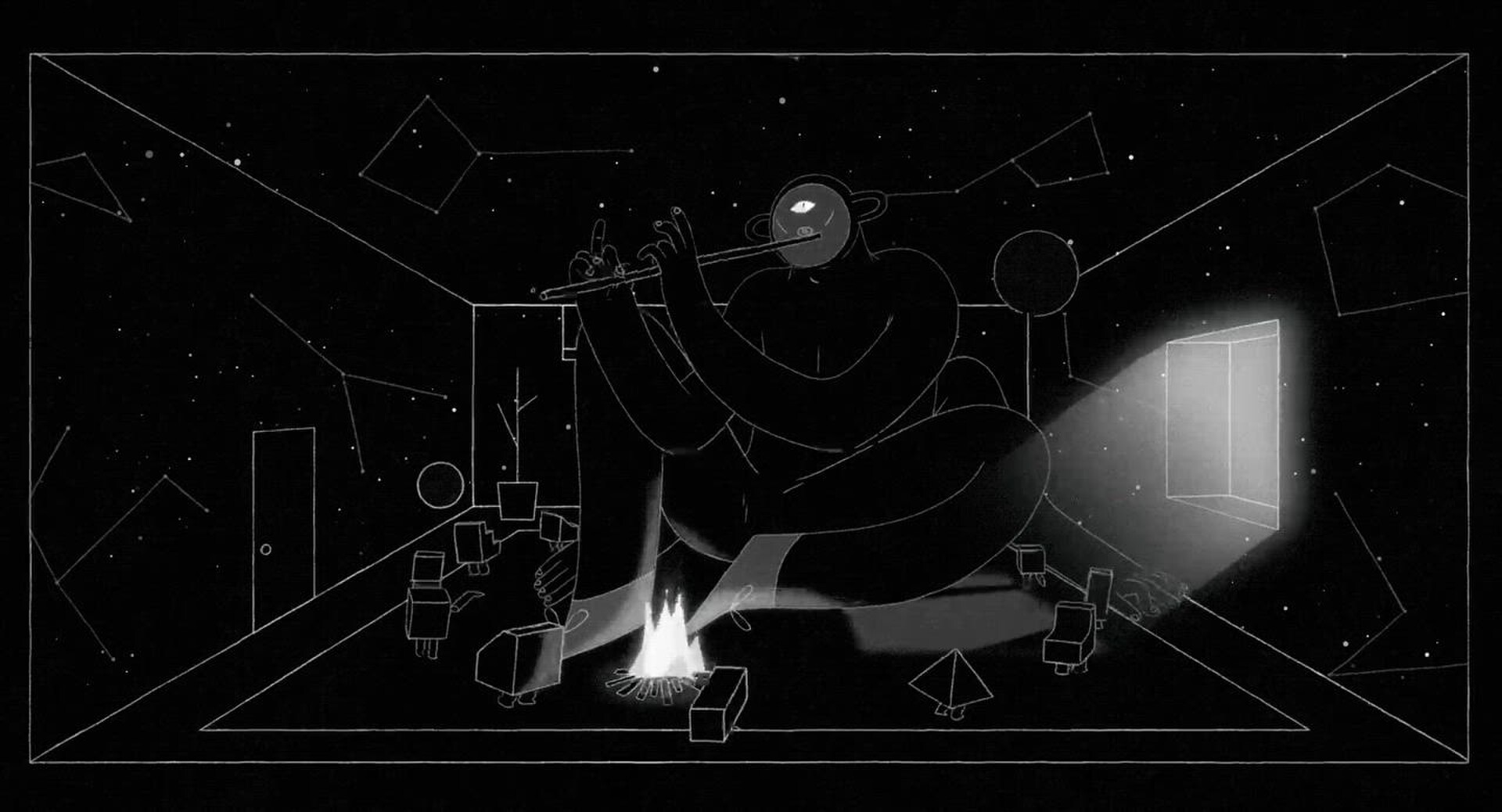

Novelli’s intense question mirrors the gloomy mood of his shorts, chief among them his most recent work, De Imperio. The title is indicative of the world of empire and control we are made to enter. Giants overlook small, angular characters who skitter and hide. When unsupervised, these chess piece-like shapes slowly stick together to form a new giant that might eventually topple the old boss. The director and his team of animators render these scenes in gorgeous, high-contrast black and white, while sound designers Simon Smith and Jonathan Darch lend the initially powerless triangles, squares, and L-shapes an audible fragility that Alessandro calls “the crystal sound”. There is a clarity of design that, for all its allegorical content and nonlinear story, sets De Imperio apart from other animated shorts.

Hailing from Italy, Novelli is now based in Porto with his partner and their eight-month-old child, both of whom accompany him to our interview. He started in graphic design and worked on commercials before finally finding his way into animation. “The interest developed over the years and refined over time”—the process of animation, rather than a particularly influential film, is what led him down this path. In the past, his work has also appeared in commissioned videos for outlets like The Atlantic and NPR; these shorts-for-hire, too, show his political bent, illustrating arms manufacturing and voting rights issues in his characteristic grayscale.

When I ask him about his animation technique, he speaks in an often pragmatic, if not self-effacing manner. Why are the previous entries in the trilogy animated in 3D, whereas De Imperio is not? “The first two shorts are developed around a single take, so 3D is much easier to handle.” What is each short’s starting point? “It starts generally with an idea that I think is kind of basic, and then a visual metaphor is added to that idea.” Why black and white? “That’s the question that everyone asks.” The directness is appropriate enough, given Novelli’s interest in Russian constructivism, an art movement of the early 20th century that eschewed ornateness in favor of stark, simple geometry that underlined the style’s political bent.

Panopticon, leviathan, chess boards, and borders: watching De Imperio sets the viewer’s mind alight with references to political theory and imagery. Yet the short is never content to reside too comfortably in allegory: for every metaphorical scene of a giant clawing its way inside a house, destroying it in the process, there is a news anchor spewing garbled fake news (and eventually spiders, which is neither here nor there). Novelli does not give a direct answer as to how he straddles this exact line, and I don’t press him: it seems obvious he cares deeply about these systems of control and tackling them in ever-evolving ways, even if there is no rock-solid strategy.

De Imperio forms the third and final part of a loose trilogy, starting with the 3D-rendered Kafka adaptation The Guardian and continuing with Contact, in which computer animation and mixed-media collide. Styled as a trilogy on human consciousness, Novelli states that “it’s an evolution of the being from the singular to the plural”—where The Guardian’s protagonist stands alone, by the time we arrive at De Imperio, the problem of consciousness becomes a collective one.

None of these films are particularly cheery, casting a doubtful light on matters of agency and our capacity for societal change. The filmmaker agrees—after he asks me for my own interpretation—that the “history repeating itself” ending of this short is a sinister one. For him, political renewal often only serves up a worse version of what came before. Just like the one that forms throughout the film, “all the other giants are also made up of pieces”—meaning the overlords are made by the very people hoping to overthrow them. “I hope it changes, but I have a pretty pessimistic view of the short.”

© De Imperio (Alessandro Novelli)

But for all its doom and gloom, Novelli’s work is marked by a stark beauty. The monochrome colour palette, he explains, keeps unwanted associations at bay while also allowing for his favorite visual element to take center stage: light. A previous short, tellingly titled Lights, is designed entirely around shafts of illumination that cut through the frame; the floodlight eyes of De Imperio’s towering antagonists are as frightening as they are sublimely beautiful. Finding beauty in eeriness is a recurrent aspect of his work: as shapely characters merge into a larger creature, they lose individuality and mobility, but create a marvel of sight and sound.

Perhaps it is this splendor that allows some viewers to get caught up in the visuals and come away with an interpretation contrary to Novelli’s. I ask how De Imperio has been received so far, knowing the film has enjoyed a substantial festival run after its premiere in Locarno, but only for him to reveal that “some people told me, ‘ah, cool, so everything will start back in a cool way.’ So for them, it’s a kind of optimistic thing.” Clearly, both of us would disagree, but the director appears at peace with this openness. “I like films that give you the chance to reflect and give you the possibility to be read in the way your life is at that moment.” Once again, ambivalence is the name of the game.

As we look at our surroundings—children playing near our café in a sunny Vienna courtyard—Novelli muses that systems of control are, ultimately, self-imposed and as limited as they are limiting. “Children play, but adults don’t play in the same way. Why?” The giants in De Imperio, he says, are deliberately framed within a clearly defined box, a visual limit imposed on these seemingly all-powerful figures. In much the same way, the initially large and bulbous protagonist of Lights forces himself into angular costuming to mirror a narrowing of possibilities in life. That these themes and images of power and control unfailingly shine through speaks to the clarity of design that forms the rock-solid basis of his work.

Even though he doesn’t always express his ambivalent feelings in the moment, Novelli and I ping-pong between the freedom offered by short films and the insular ecosystem in which they are made and exhibited; he outlines his strong foundation in thematic and visual design only to then worry if his previous shorts have been too “concept-driven” and hence not accessible enough for all their political punch. I get the impression that he is at once in awe of the power of the image and wary of most other forms of power—including, it seems, that of the critic.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #4—a tandem workshop set during Filmfest Dresden and Vienna Shorts—and edited by tutor Anas Sareen.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.