Resistance Through Intimacy

Mast-del

Gestures of love reach further than any demonstration of hate in Mast-del, an experimental poem about forbidden desires, both inside and outside post-revolution Iranian cinema.

Maryam Tafakory’s Mast-del is a scream wrapped in a cinematic whisper. The Shiraz-born filmmaker presents a story (re)told between two women in bed right before the sun rises—an act of revisiting a traumatic event to understand it better and to stop its memory from fading away: when a cinephile girl (unnamed) meets a cinephile boy (named Ali) in a snowy park, their innocent date brings brutal consequences for both parties. Of course, external forces are at fault. Mast-del invites the audience to retrace this episode of budding love step by step.

For the women narrators in Mast-del, this recollection starts with a trigger: a sensation and a sound. With gusts of wind storming in their room, they wake up. It sounds like someone knocking at the door: stirring up one the same way snow (as we’re then told) sets off the other woman, as reminders of past traumatic experiences we know nothing of yet. But Tafakory keeps us close to her characters, taking the audience on an immersive journey of reenacted feelings, conveyed first through sound and only then, through narration.

As the story develops, the soundscape shifts: starting with incessant gusts of wind and waves crashing, they eventually subside, leaving room for a musical embrace. Sarah Davachi’s “Magdalena” is a track that, through its melodic movement of escalation and de-escalation, is on itself also like a wave (that comes and goes) until all that’s left is a subtle interference. In this sound, too, Mast-del locks the remains of a bygone time, the residue of past (and present) noises. The soundscape then goes back to where it started: the wind returns, but the healing journey is still ongoing.

As we’re carried by this simple yet unique sonic vessel, the narrating voices appear on screen as subtitles. We read the dialogue between these two women, doubled in Farsi and English, their colour and font type varying. Yellow italics portray direct speech within the story; white standard denotes the omniscient narrator’s perspective of the different episodes that are being presented.

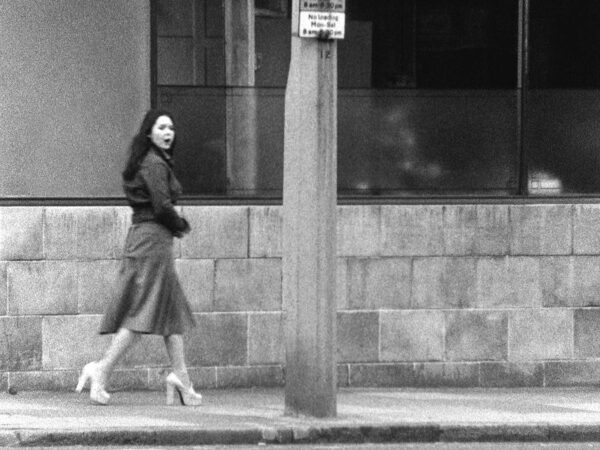

This is a tale of trauma, but not exclusively. The short’s overall narration does include that remnant of a painful past, but making it a story shared between two women gives us a glimpse of a present intimate tense. Mast-del, as a film about memory, is itself a very particular capsule of time. Most of the images have been altered in some way from their original form: using their negatives reinforces the haunting presence draping the film’s every frame.

Some ideas may not always be immediately visually translatable, which can also enrich the particular emotional and physical experience of watching the film. From the abstract can come a sense of clarity. This might sound paradoxical, but it is vital: letting the textures and web of emotions find their way beyond the screen, knowing there’s a connection between scenes with these women and scenes with others.

© Mast-del (Maryam Tafakory, 2023)

Cinema can be a key that untangles all possible knots, a tool of and for connection. These women are not alone but connected with what has come before them and what is still in their beds, minds, and bodies. This is both their past and present, inscribed by cinematic history. A clever montage blends the story with scenes from Iranian post-revolutionary films (from 1982 until 2010) that compose and reflect the collective, cultural Iranian memory.

But we confront it from up close: yes, close-ups frame only certain elements, scenes, and films within that cinematic tradition. Perhaps not getting the full picture creates an even bigger one with the help of the past. Snippets of hands in focus, even if unbeknownst to us who (and when) we’re seeing, create this unknown—but oh so familiar—impression. We metaphorically take those—their—hands and dare to move with (all of) them.

It, therefore, seems fitting that at the heart of this narration sits a short story about a date that was supposed to happen in a cinema, about a possible love coming from the shared passion for film. Cinema can be used to reenact and portray life’s obstructions. As a means to deal with trauma, it can imagine experiences without perpetuating the violence that was once inflicted.

It feels both therapeutic and blissful to find yourself so close to scenes of tactile exchanges that it seems like you can, in turn, return the touch. Even more so if the possibility of desire and its actualisation through physical contact were the bearers of trauma in the first place. One can exchange touch with objects (a cup, a door handle, a cigarette, a wall) or someone else. In those cases, it can either transform into a shield (to close the door, protecting yourself) or also mainly to allow yourself to get back in (opening the door, as nobody will knock). Gestures of love that reach further than any demonstration of hate. Those are the gestures that will resist through time: this is where they—and we all—can be (or feel) safe.

As the film fades, we’re still moved by the waves. Mast-del is a testament to resistance through intimacy. And we—as they—will dare to stay.

There are no comments yet, be the first!