Return to Cuckooland

Nikola Ilić on Exit Through the Cuckoo’s Nest

Composed mainly of archival footage, Nikola Ilić’s personal essay documents the story of a soldier who never wanted to be one.

True to Swiss punctuality, Nikola Ilić arrives at the Vienna Shorts guest desk early. He has a couple of films showing at the festival and kids to look after, so I suggest we head to the café around the corner. He orders a cappuccino while I practice my German, ordering a großer Schwarzer. Nikola’s English is confident, and his direct tone a reminder of his Balkan roots.

There are lines in his Serbian voice-over track for Exit Through the Cuckoo’s Nest that, to my mind, could readily inspire standalone adaptations. Nikola’s short film is an energetic essayistic documentary about his teenage years and early adulthood in Serbia in the 1990s. After the Bosnian War, Serbia invaded Kosovo. NATO intervened, dropping some 23,000 bombs on Milošević’s forces. Nikola was brought up in a country crippled by sanctions and conscripted in the latter war. I’m interested in the tension between memory and storytelling: how much of what we see on screen is pure recollection? “Memories are always split into good ones and bad ones,” he says. “And the bad ones, we try to bury somewhere.”

Childhood innocence, marred by the experience of war, is a theme in Nikola’s life. He remembers colours and smells vividly—faces and names escape him. He was just 15 when the Bosnian War started, 18 when the Dayton Accords were signed, and 21 when the Kosovo War erupted. Even so, he notes that his upbringing in Belgrade was like living in a bubble, detached from the immediate chaos of these tumultuous events. He dreamt of becoming a professional skateboarder, though he hurriedly admits he wasn’t “that good”. Photography then became another passion of his, perhaps anticipating his future as a filmmaker.

A city boy in the Serbian army composed primarily of countryside dwellers “horny” for war, Nikola doesn’t quite fit the standard recruit profile. He had emerged from the straight-edge subculture. “We don’t drink, we don’t take drugs, we are totally free of that,” he explains, with a tinge of pride, his allegiance to the punk underground scene. His band, ‘To Live For’, defiantly embraced self-expression, a stark contrast to the regimented military life defined by the conformity that was to come. Brought up on the edge of the Senjak neighbourhood in Belgrade, surrounded by embassies, Nikola was influenced by a melding of cultures. He was “more poor than rich”, but remembers his childhood fondly, especially the music.

The film had to kick off with concert footage; this much was crystal clear to Nikola the moment he realised he would be staging himself as the film’s central character. The original premise, centered on individuals fixated on war and glorifying firearms, seems like a detour in hindsight. Yet, in truth, the shift in interest was abrupt. During the funding application process in Switzerland, Nikola included his director’s motivation in the required dossier, and funding bodies showed more interest in the personal narrative than the original film concept.

When it comes to the making of Cuckoo’s Nest, he says it was important for him to create something beyond “an audiobook with visuals”. Helpfully, he has a close rapport with his key collaborator, the editor: Corina Schwingruber Ilić is both his wife and a frequent creative partner. She, too, encouraged Nikola to pursue his personal story. So did fate. During visits to Belgrade over the past two years, he encountered several people who had fled Ukraine and Russia following the outbreak of war in 2022. He saw his own reflection in them. “I can’t hide behind their stories; I have to tell mine.” The revelation led him to a process that recalls that behind DIDA (2021), his sole feature film to date, and a story about his mother, who lives in Serbia. During the shoot, his grandmother’s sudden death led him to put himself in front of the camera, a role originally intended for her. “It’s like a striptease,” he confides.

© Exit Through the Cuckoo’s Nest (Nikola Ilić)

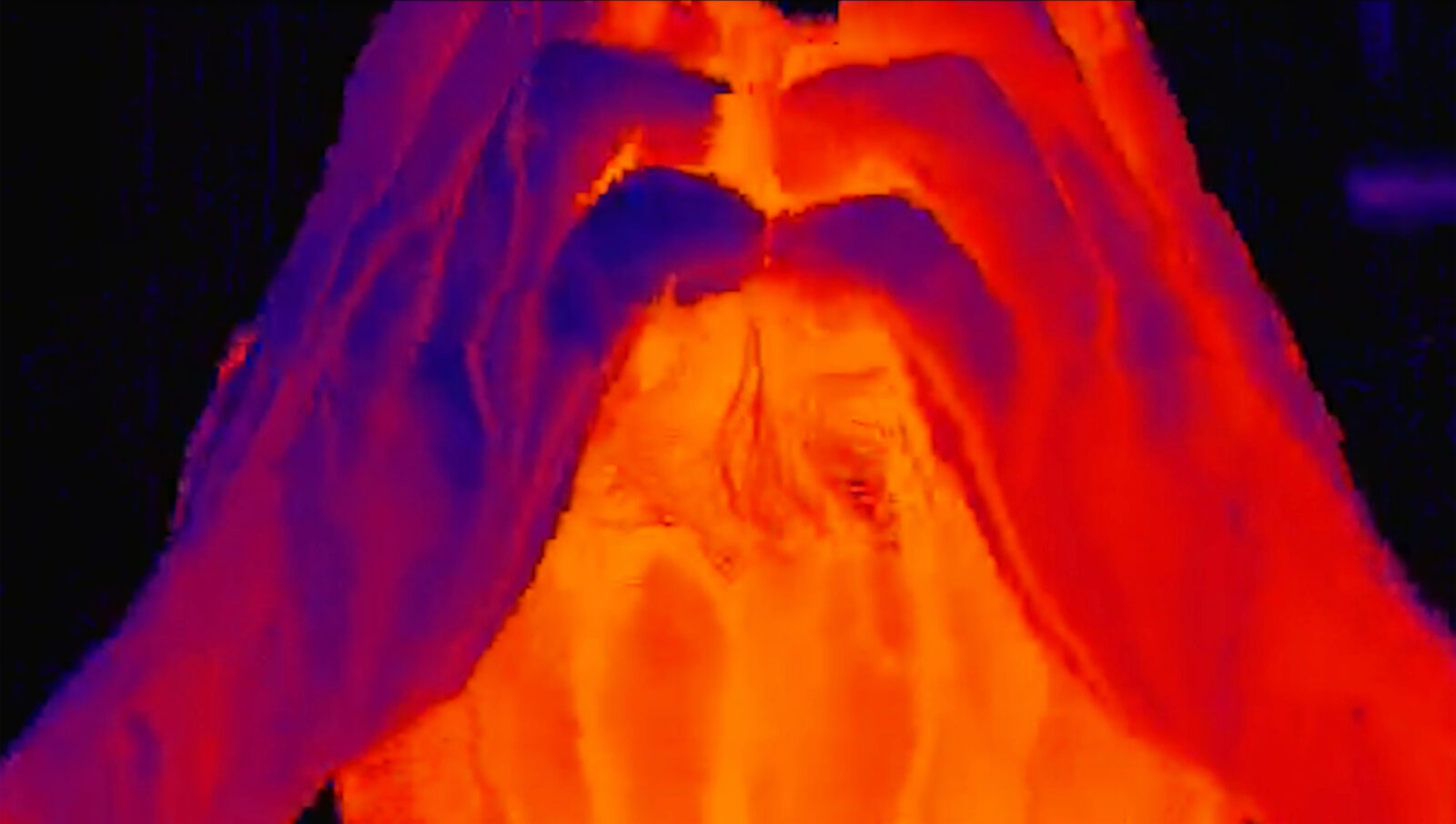

Cuckoo’s Nest is Nikola’s most recent act of vulnerable autobiography. It’s designed as a maze of colourised surveillance footage, personal camcorder videos, and contemporary documentary scenes. The blend of the personal and the anonymous serves as a compelling canvas for the filmmaker’s voice-over narration. It accentuates the spoken words while leaving ample room for the viewer’s imagination, like some sort of sheer fabric.

When I enquire about his key inspirations, he takes a moment and recalls Peter Liechti’s The Sound of Insects, a 2009 Swiss film about a man suicide by starvation. Initially drawn to its intimate diary format, Nikola ultimately picked a different path, one in which spontaneity was embraced. The thermal camera photography, for instance, was just “really cool” to him. Cuckoo’s Nest continued to evolve during editing, responding to external events, when provocative graffiti appeared across Belgrade with a message: “When Serbian military returns to Kosovo…” Nikola doesn’t know if he was more afraid of killing someone or getting killed; music, his band, and skateboarding helped him preserve his principles. “I think it takes two, even three generations to heal the wounds,” muses the pacifistic war veteran.

I ask the question that needs asking: does he see himself as a Serbian or a Swiss filmmaker? “I’m just a filmmaker,” he replies, toying with his bag of sugar. He enjoys transitioning between the chaos of Serbia, his affective anchor, and the order of Switzerland, where he lives. Switzerland doesn’t fully feel like home, however; the name ‘Ilić’ still relegates him to the potentially derogatory ‘Yugo’ ethnic category. Ironically, Swiss prejudice elides Balkan differences, as though those who emigrated from the former Yugoslavia suddenly belonged to one unified nation. We share a complicit chuckle. “The new generation doesn’t really give a damn,” Nikola remarks when reflecting on the more accepting attitude he has witnessed in Swiss youngsters.

The film’s final frames cast a more doubtful shadow on this otherwise hopeful assessment: a new generation of young Serbian skateboarders continues to roam the streets of Belgrade, unfazed by the warmongering graffiti that today serves as a backdrop to their stunts.

Nikola is a generous interviewee, though, every once in a while, he pauses to reflect: “I talk too much…” He confesses that he plans to move away from personal stories and focus on ideas collected from others. While researching Cuckoo’s Nest, he met several people who shared similar wartime experiences and wore “the same boots.”

As I turn off the recording and he puts his sunglasses back on, I have the feeling he will soon return to his personal trenches because storytelling for Nikola Ilić is an affair that needs to begin with the self.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #4—a tandem workshop set during Filmfest Dresden and Vienna Shorts—and edited by tutor Anas Sareen.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.