A Fishbowl of Fuckery

Hito

A constant bombardment of stimuli, Stephen Lopez’s dystopian talking fish bromance is all the more interesting for its political undercurrents.

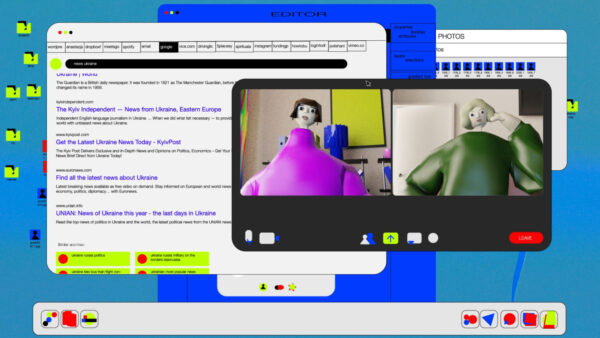

A buff anthropomorphic catfish manifests itself on a Dresden cinema screen and curses, to one German viewer’s astonishment. She releases a strangled “Was ist das?!” from the back of the room, killed by the upsurge of chuckles. She’s got a point, though. Hito is a freak show.

This short Filipino film, written and directed by Stephen Lopez, follows a well-worn formula: girl, Jani, meets catfish, Kiefer, in comradeship. “Buy us something for dinner”, requests girl’s mother, but the food Jani gets ends up snatched by a floating Japanese-speaking shih-tzu dog. Its owner, possibly an alternative reality dweller, gifts the girl a red pill… the eponymous Hito, as compensation. A sequence of off-beat twists and turns, this opening is but an appetiser before visual psychedelia fully kicks in.

Lopez’s Philippines is a militarised police state with poor radiation forecast. Cinematographer Akie Yano’s scene-setting wide shot captures kids playing and fighting in front of nuclear reactors. A public address system warns everyone to stay home except during designated hours; otherwise, only those with special permits can wander outside.

As if Jani did not have enough going on, the fabric of her reality is literally disintegrating. It is interrupted by surreal glitches, aesthetically placed between hyper-ironic YouTube montages and Everything Everywhere All at Once’s multiverse travels. It is as though the film is ready to self-destruct. With every new ‘glitch’ breaking up Jani’s reality, we might be increasingly more tempted to consider George Lucas’ famous “I might have gone too far in a few places” quote. The device is at once amusing and bewildering, at least until Lopez finally justifies it in a true B-movie fashion: in Hito, the state is after people’s minds.

Let’s glitch back to Jani’s fish purchase for a moment. The man who sells Jani the fish has an innocent print on his RoboCop T-shirt that reads, “Say no to drugs”. The public address system and billboard slogans make mention of harsh curfews. Innocent as these seem if decontextualised, they can hardly be coincidental in the Philippine context. The country’s former president Rodrigo Duterte’s “war on drugs” was a period of extra-judicial killings. Later, his government’s draconian lockdown placed the country under armed rule, with punitive measures that resembled those of the severe anti-drug campaign. Reports emerged of kids stuffed inside coffins or confined to dog cages for violating regulations.

But back to the mind games. In the short’s longest scene, we find Jani tied to a chair in a white room decorated with interrogation machinery. It’s a very Clockwork Orange-esque setup. The maniac who runs the show, tellingly called the Director, comes in and promises not to brutalise Jani, though he remains inquisitive about the location of the “terrorist asset” she is hiding: Kiefer, the talking catfish. But Jani does not seem content with the narrative the Director provides her with and keeps questioning the reality she finds herself in. She decidedly refuses to embrace the totalitarian society on offer. The Director seems keen to explain what the larger purpose and benefits of their operation are, but Kiefer bursts in to rescue Jani and the bi-species duo beats the crap out of the Director, generously sprinkling the room with blood.

The last scene figures a humorous denouement, with Kiefer and Jani eating inside a studio-lit, motionless car. And finally, the viewer gets to catch their breath. Is this the moment to consider the film’s latent implications? After all, the Director name-dropped the martial law period and by this stage, we have been told that the glitches are not merely a gimmick but a representation of Jani’s disagreement with the reality the government is presenting her with. Entertaining and story-relevant? Yes. But, again, not so innocent a choice.

Jani, whose young age suggests she would have been removed from the period of martial law trauma, is ripe for historical ‘rehabilitation’. She makes for a natural target in the Philippines, where the infamous Marcos family, responsible for the days of martial law half a century ago, weaponised platforms, including social media, to whitewash their violent history. In a uniquely absurd bid for revisionism, their defenders waged ‘edit wars’ on the family’s Wikipedia. Boosted by online disinformation campaign, Marcos Jr., son and namesake of the tyrannical Marcos Sr., won the Philippine presidential office. This legacy of historical fuckery is one that Hito picks up on and exaggerates.

Can Hito’s world owe its wackiness to big historical and political claims? Probably not on the first viewing. For some viewers, maybe not at all. The film is a constant bombardment of stimuli. It is, first and foremost, a wicked genre exercise that endearingly weaponises its B-movie key: catfish-suit-wearing giants, dystopian landscapes, and moments of unapologetic farce. Lopez’s berserk vision is quite unique, and, to me, all the more interesting for its political undercurrents.

So, again, was ist das? Two answers. The obvious one: a dystopian talking fish bromance. And an equally valid one: a wacky political commentary with hidden layers of meaning.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #4—a tandem workshop set during Filmfest Dresden and Vienna Shorts—and edited by tutor Anas Sareen.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!