Nervous Anticipations

The Bite

Cross-referencing politics and body politics, reproduction and pandemics, Isadora Neves Marques creates a juxtaposition between a warning dystopia and a dangerous reality.

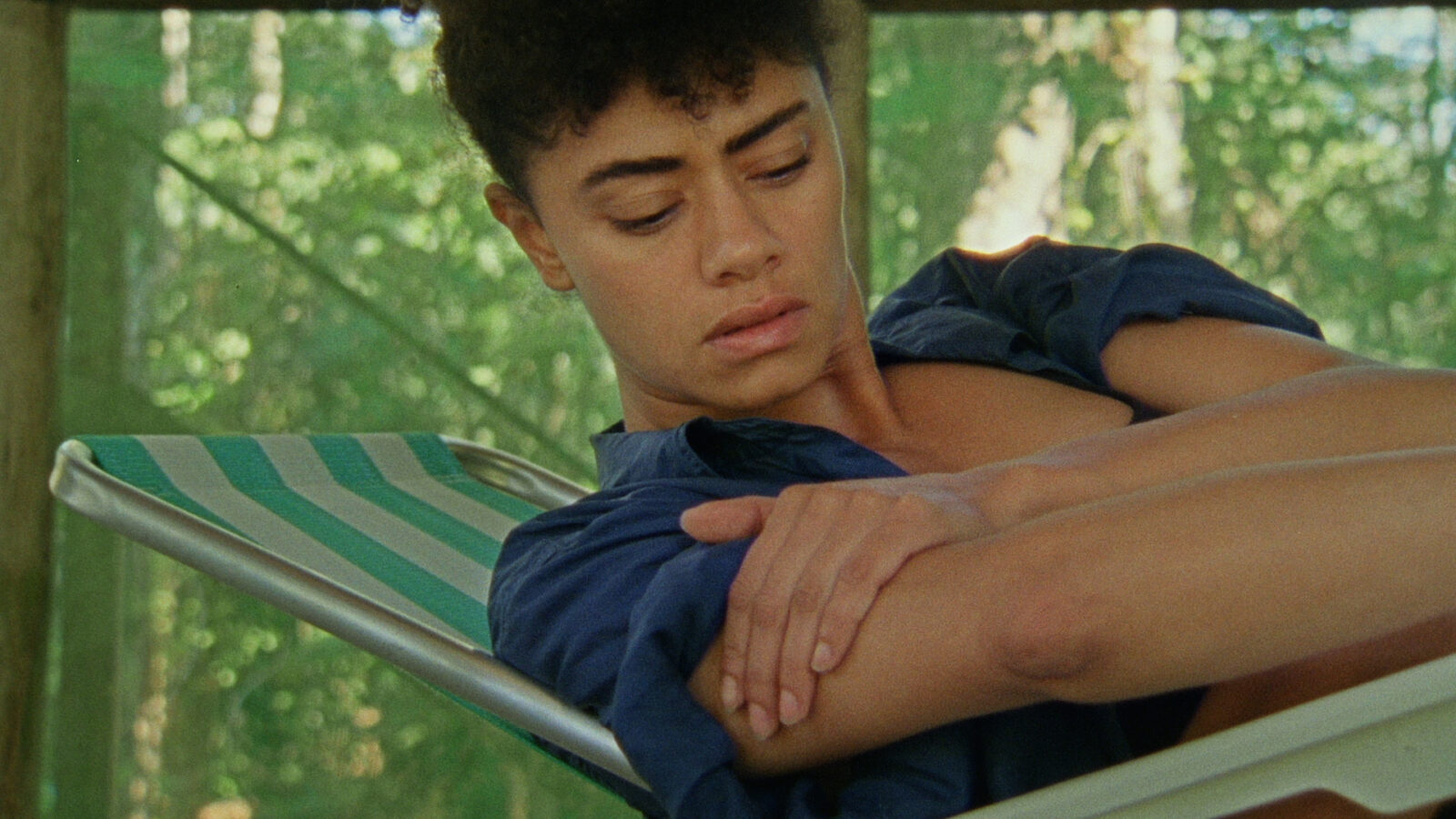

Isadora Neves Marques’ 16-mm film The Bite covers a lot of ground: (bio)politics, gene engineering, pandemics, sexuality, ecology, and extractivism. It all boils down to tension, intensified by its original score—jittery, pulsating, suspicious.

We meet a transgender woman named Tao, cisgender woman Calixto, and the biologist Helmut—all involved in a triangle relationship. The plot unfolds simultaneously in a forest house (inhabited by both women) and a lab near São Paulo. There, Helmut and his colleague are experimenting with genetically engineered mosquitoes: releasing them into nature could potentially stop a virus carried out by infected mosquitoes. Though Marques doesn’t specify the virus, the similarities with the Zika virus, which marked 2015 and 2016 in Brazil, are apparent.

Marta Simões’ images are hypnotic. Dominated by different shades of white (in the lab) and green (outside of the lab), they remind us of a floral oasis artificially planted in a secluded glass vase. This metaphor equally applies to the world portrayed in this film: even though The Bite touches upon relevant current socio-political issues, the heroes seem to live as far as they can from the real world—in a vacuum.

This Side of the Net

The net, where both the house and the lab are located, is meant to protect. But this “inside” is also a place for discomfort and bad presentiments. The physical net is the prime warning sign, serving as a brittle wall, promising a fragile shelter from the outer world weakened by the epidemic. Tao observes a snuck-in mosquito through it: the insect is banging against a jade-green wall, enhancing nervousness and suspense for both her and the viewer.

Fear increases when Calixto gets bitten, more so when we learn that the couple (or throuple) might be expecting, as Tao is reading about embryo development. Zika is dangerous for expecting women, causing severe complications, one of them being incomplete brain development (in which the child is born with a smaller head). Brazil’s health system is trying to deal with so-called Zika babies and treat their neurological disabilities. Yet, anti-abortion laws remain, and women need to proceed with the pregnancy, even if they’ve been diagnosed with the virus.

Meanwhile, Helmut’s colleague refers to the epidemic as “this unstoppable thing,” pointing out that they’ve been working on an antidote for years. Anxiety lies in hopelessness, which is why Helmut uses a physical net as a shield. The protective clothing allows the scientist to release the transgenic mosquitos into the wild threat-free. Nonetheless, unease never disappears.

This ever-present tension escalates in the closing sequence when the threesome—Calixto, Tao, and Helmut—engages in a sexual act. Despite the assumed safety “this side of the net” should provide, their bodies struggle to come closer together, acting stiff and avoidant certain kinds of caresses. Contemporary Brazil’s face might be pulsating in the back of their brains. They want to be sexually liberated but take two steps closer to each other and then retract one.

The Other Side of the Net

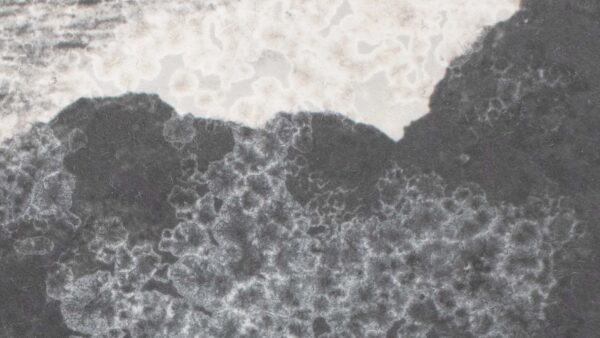

The virus scare is the visible layer of the onion. But Neves Marques digs deeper, making “the other side” unstable and worrying. Nature feels menacing, and long screen time emphasises the water source and the dark, unwelcoming forest. Water can be a potential breeding nest for mosquitos, as they prefer to lay their eggs in stagnant liquid. The surrounding forest suggests someone hiding there—marked specifically by Marques’ long, focused zoom-ins. When Tao goes for a swim, the camera is placed behind the trees, imitating the voyeuristic gaze of a predator waiting for the right moment to attack. The feeling that someone’s (been) watching never leaves us.

Distress about the outside world grows when Calixto evaluates the situation in São Paulo as bad—the military forces are everywhere. Now we have this monster taking over the country,” one of the scientists states. Harmful politics and biopolitics are comparable to pandemics as they both demand complete control over every aspect of an individual’s health, free will, and movement.

The resemblance between the world created in the film and today’s Brazil is inevitable. Brazil’s complex socio-political situation has worsened tremendously under the reign of extreme right president Jair Bolsonaro, who has also proudly claimed himself to be a homophobe. Even in a secluded house, the principal trio cannot unwind to a full extent, knowing that an anti-democratic sentiment suppresses their passion, freedom, and gender expression.

Trans* people in Brazil are common victims of hate crimes and murders. Journalist Oscar Lopez writes that Brazil “regularly ranks as the deadliest country worldwide for trans* people” and that the social prejudice has worsened under Bolsonaro’s presidency, who publicly speaks against “progressive ideas on sex and gender.” This topic gained extra attention after the release of J.K. Rowling’s new book Troubled Blood (written under her pseudonym Robert Galbraith), which tells a story about a transvestite serial killer. Rowling’s freshest novel received backlash and accusations of transphobia that had British trans activist Paris Lees tweeting: “Meanwhile over in the real world the number of trans people killed in Brazil has risen by 70% this past year, young trans women are left to burn in cars and men who kill us (for being trans) are pardoned and sent home.”

Toxic Dominations

The Bite reflects on poisonous masculinity as a destructive force. After all, the male mosquito is injected with the lethal gene—a (supposed) guarantee that the female it will mate with won’t carry a living offspring. Gene engineering helps to eliminate undesirable characteristics, such as females carrying the virus. It can be interpreted as an attempt to control and homogenise the entire population, which draws strong parallels with policies and technologies that increasingly affect the demography and reproduction. Said manipulations determine the next generations of humans, plants, and animals, interfering with nature’s way of taking care of them. Tao, as a transgender character, serves as a protest against this categorization and homogenization.

Tao is the most dominant but doesn’t use this trait for control. Helmut, however, tries to catalyse some minor disturbance in their dynamics. When the cisgender male joins the couple, their balance shifts, thickening the tension. Calixto seems more comfortable with Tao, sometimes leaving Helmut behind on the edge of the bed. Helmut’s views on warfare are linked to this toxic domination. He states that it’s not enough to send soldiers when invading another country: “You send soldiers, tanks, aeroplanes, bombs.” The epidemic is compared to a violent invasion, suggesting that the human and moral factors are inexistent.

Mosquitos are a blood-sucking parasite, and so is extractivism. Marques’ film points out the environmental issues and land destruction caused by it: in South America, extractivism has harmed the ecosystem and local farmers. Different shades of tension mark the film, from nervousness to fear, aggression to hopelessness.

The Bite highlights the filmmaker’s ability to create magical and terrifying universes filled with codes, secrets, and hidden messages about some of today’s most relevant issues. Cross-referencing politics and body politics, reproduction and pandemics, she ultimately creates an opiate juxtaposition between a warning dystopia and a dangerous reality.

There are no comments yet, be the first!